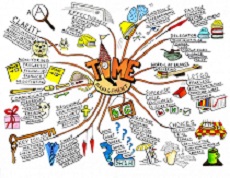

The hidden human senses

The student of occultism usually is quite familiar with the crass individual

who assumes the cheap skeptical attitude toward occult matters, which

attitude he expresses in his would−be "smart" remark that he "believes only

in what his senses perceive." He seems to think that his cheap wit has

finally disposed of the matter, the implication being that the occultist is a

credulous, "easy" person who believes in the existence of things contrary to

the evidence of the senses.

While the opinion or views of persons of this class are, of course, beneath

the serious concern of any true student of occultism, nevertheless the

mental attitude of such persons are worthy of our passing consideration,

inasmuch as it serves to give us an object lesson regarding the childlike

attitude of the average so−called "practical" persons regarding the matter of

the evidence of the senses.

These so−called practical persons have much to say regarding their senses.

They are fond of speaking of "the evidence of my senses." They also have

much to say about the possession of "good sense" on their part; of having

"sound common sense"; and often they make the strange boast that they

have "horse sense," seeming to consider this a great possession. Alas, for

the pretensions of this class of persons. They are usually found quite

credulous regarding matters beyond their everyday field of work and

thought, and accept without question the most ridiculous teachings and

dogmas reaching them from the voice of some claimed authority, while

they sneer at some advanced teaching which their minds are incapable of

comprehending.

Anything which seems unusual to them is deemed "flighty," and lacking in appeal to their much prized "horse sense."

But, it is not my intention to spend time in discussing these insignificant

half−penny intellects.

I have merely alluded to them in order to bring to

your mind the fact that to many persons the idea of "sense" and that of

"senses" is very closely allied. They consider all knowledge and wisdom as

"sense;" and all such sense as being derived directly from their ordinary

five senses. They ignore almost completely the intuitional phases of the

mind, and are unaware of many of the higher processes of reasoning.

Such persons accept as undoubted anything that their senses report to them.

They consider it heresy to question a report of the senses. One of their

favorite remarks is that "it almost makes me doubt my senses." They fail to

perceive that their senses, at the best, are very imperfect instruments, and

that the mind is constantly employed in correcting the mistaken report of

the ordinary five senses.

Not to speak of the common phenomenon of color−blindness, in which one

color seems to be another, our senses are far from being exact. We may, by

suggestion, be made to imagine that we smell or taste certain things which

do not exist, and hypnotic subjects may be caused to see things that have no

existence save in the imagination of the person.

The familiar experiment of the person crossing his first two fingers, and placing them on a small

object, such as a pea or the top of a lead−pencil, shows us how "mixed" the

sense of feeling becomes at times. The many familiar instances of optical

delusions show us that even our sharp eyes may deceive us−−every

conjuror knows how easy it is to deceive the eye by suggestion and false

movements.

Perhaps the most familiar example of mistaken sense−reports is that of the

movement of the earth. The senses of every person report to him that the

earth is a fixed, immovable body, and that the sun, moon, planets, and stars

move around the earth every twenty−four hours. It is only when one

accepts the reports of the reasoning faculties, that he knows that the earth

not only whirls around on its axis every twenty−four hours, but that it

circles around the sun every three hundred and sixty−five days; and that

even the sun itself, carrying with it the earth and the other planets, really

moves along in space, moving toward or around some unknown point far

distant from it.

If there is any one particular report of the senses which

would seem to be beyond doubt or question, it certainly would be this

elementary sense report of the fixedness of the earth beneath our feet, and

the movements of the heavenly bodies around it−−and yet we know that

this is merely an illusion, and that the facts of the case are totally different.

Again, how few persons really realize that the eye perceives things

up−side−down, and that the mind only gradually acquires the trick of

adjusting the impression?

I am not trying to make any of you doubt the report of his or her five

senses. That would be most foolish, for all of us must needs depend upon

these five senses in our everyday affairs, and would soon come to grief

were we to neglect their reports. Instead, I am trying to acquaint you with

the real nature of these five senses, that you may realize what they are not,

as well as what they are; and also that you may realize that there is no

absurdity in believing that there are more channels of information open to

the ego, or soul of the person, than these much used five senses.

When you once get a correct scientific conception of the real nature of the five

ordinary senses, you will be able to intelligently grasp the nature of the

higher psychic faculties or senses, and thus be better fitted to use them. So,

let us take a few moments time in order to get this fundamental knowledge

well fixed in our minds.

What are the five senses, anyway. Your first answer will be: "Feeling,

seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling." But that is merely a recital of the

different forms of sensing. What is a "sense," when you get right down to

it? Well, you will find that the dictionary tells us that a sense is a "faculty,

possessed by animals, of perceiving external objects by means of

impressions made upon certain organs of the body." Getting right down to

the roots of the matter, we find that the five senses of man are the channels

through which he becomes aware or conscious of information concerning

objects outside of himself.

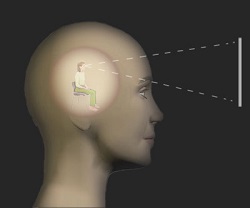

But, these senses are not the sense−organs alone.

Back of the organs there is a peculiar arrangement of the nervous system, or

brain centres, which take up the messages received through the organs; and

back of this, again, is the ego, or soul, or mind, which, at the last, is the real

KNOWER. The eye is merely a camera; the ear, merely a receiver of

sound−waves; the nose, merely an arrangement of sensitive mucous

membrane; the mouth and tongue, simply a container of taste−buds; the

nervous system, merely a sensitive apparatus designed to transmit messages

to the brain and other centres−−all being but part of the physical machinery,

and liable to impairment or destruction. Back of all this apparatus is the real

Knower who makes use of it.

Science tells us that of all the five senses, that of Touch or Feeling was the

original−−the fundamental sense. All the rest are held to be but

modifications of, and specialized forms of, this original sense of feeling. I

am telling you this not merely in the way of interesting and instructive

scientific information, but also because an understanding of this fact will

enable you to more clearly comprehend that which I shall have to say to

you about the higher faculties or senses.

Many of the very lowly and simple forms of animal life have this one sense

only, and that but poorly developed. The elementary life form "feels" the

touch of its food, or of other objects which may touch it. The plants also

have something akin to this sense, which in some cases, like that of the

Sensitive Plant, for instance, is quite well developed. Long before the sense

of sight, or the sensitiveness to light appeared in animal−life, we find

evidences of taste, and something like rudimentary hearing or sensitiveness

to sounds.

Smell gradually developed from the sense of taste, with which

even now it is closely connected. In some forms of lower animal life the

sense of smell is much more highly developed than in mankind. Hearing

evolved in due time from the rudimentary feeling of vibrations. Sight, the

highest of the senses, came last, and was an evolution of the elementary

sensitiveness to light.

But, you see, all these senses are but modifications of the original sense of

feeling or touch. The eye records the touch or feeling of the light−waves

which strike upon it. The ear records the touch or feeling of the

sound−waves or vibrations of the air, which reach it. The tongue and other

seats of taste record the chemical touch of the particles of food, or other

substances, coming in contact with the taste−buds. The nose records the

chemical touch of the gases or fine particles of material which touch its

mucous membrane.

The sensory−nerves record the presence of outer

objects coming in contact with the nerve ends in various parts of the skin of

the body. You see that all of these senses merely record the contact or

"touch" of outside objects.

But the sense organs, themselves, do not do the knowing of the presence of

the objects. They are but pieces of delicate apparatus serving to record or to

receive primary impressions from outside. Wonderful as they are, they have

their counterparts in the works of man, as for instance: the camera, or

artificial eye; the phonograph, or, artificial ear; the delicate chemical

apparatus, or artificial taster and smeller; the telegraph, or artificial nerves.

Not only this, but there are always to be found nerve telegraph wires

conveying the messages of the eye, the ear, the nose, the tongue, to the

brain−−telling the something in the brain of what has been felt at the other

end of the line. Sever the nerves leading to the eye, and though the eye will

continue to register perfectly, still no message will reach the brain. And

render the brain unconscious, and no message will reach it from the nerves

connecting with eye, ear, nose, tongue, or surface of the body. There is

much more to the receiving of sense messages than you would think at first,

you see.

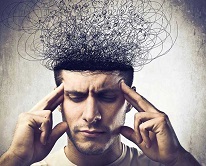

Now all this means that the ego, or soul, or mind, if you prefer the term−−is

the real Knower who becomes aware of the outside world by means of the

messages of the senses. Cut off from these messages the mind would be

almost a blank, so far as outside objects are concerned. Every one of the

senses so cut off would mean a diminishing or cutting−off of a part of the

world of the ego. And, likewise, each new sense added to the list tends to

widen and increase the world of the ego. We do not realize this, as a rule.

Instead, we are in the habit of thinking that the world consists of just so

many things and facts, and that we know every possible one of them. This

is the reasoning of a child. Think how very much smaller than the world of

the average person is the world of the person born blind, or the person born

deaf! Likewise, think how very much greater and wider, and more

wonderful this world of ours would seem were each of us to find ourselves

suddenly endowed with a new sense! How much more we would perceive.

How much more we would feel. How much more we would know. How

much more we would have to talk about. Why, we are really in about the

same position as the poor girl, born blind, who said that she thought that the

color of scarlet must be something like the sound of a trumpet. Poor thing,

she could form no conception of color, never having seen a ray of

light−−she could think and speak only in the terms of touch, sound, taste

and smell. Had she also been deaf, she would have been robbed of a still

greater share of her world. Think over these things a little.

Suppose, on the contrary, that we had a new sense which would enable us

to sense the waves of electricity. In that case we would be able to "feel"

what was going on at another place−−perhaps on the other side of the

world, or maybe, on one of the other planets. Or, suppose that we had an X

Ray sense−−we could then see through a stone wall, inside the rooms of a

house.

If our vision were improved by the addition of a telescopic

adjustment, we could see what is going on in Mars, and could send and

receive communications with those living there. Or, if with a microscopic

adjustment, we could see all the secrets of a drop of water−−maybe it is

well that we cannot do this. On the other hand, if we had a well−developed

telepathic sense, we would be aware of the thought−waves of others to such

an extent that there would be no secrets left hidden to anyone−−wouldn't

that alter life and human intercourse a great deal?

These things would really

be no more wonderful than is the evolution of the senses we have. We can

do some of these things by apparatus designed by the brain of man−−and

man really is but an imitator and adaptor of Nature. Perhaps, on some other

world or planet there may be beings having seven, nine or fifteen senses,

instead of the poor little five known to us. Who knows!

Go to Lecture 5: "Not everything is as it seems. The reality is beyond the information of our senses."

Let´s receive love and peace from all of us.

Reading Support: